Recently this past month, during MCLA’s annual Day of Dialogue, letterpress printer Amos Kennedy invited MCLA students and faculty to engage in crucial conversation around racism within our country: how one contributes to it, and how we can fight it.

Kennedy is a renowned press printer, using the art form to give a voice to minority groups usually excluded from being rightfully heard within society.

Starting off his presentation, he probed listeners, asking: “As a white student, can you name four black poets, writers, philosophers? My guess is probably not. But if you ask a black student to name four white poets, writers, philosophers? They can.” His question immediately revealed a distinction between what types of media and artists are held in high regard in American society, and which are cast aside.

After considering these racial discrepancies, the engaged audience listened as Kennedy explained his first introduction to press printing and how it changed his life’s trajectory. Originally a businessman until his forties, he found a workshop on press printing, took it, and immediately fell in love. He now has his own printing shop located in Chicago and teaches others how to appreciate and create within this art form, offering workshops and classes.

Kennedy lives by the motto: “Perfection is an illusion.” In his teaching, he inspires students to embrace the ‘imperfections’ within their pieces.

In press printing, he found a niche way to incorporate his art with his culture, explaining, “I identify with the oppressed, and as such, my voice is the voice of the common people.”

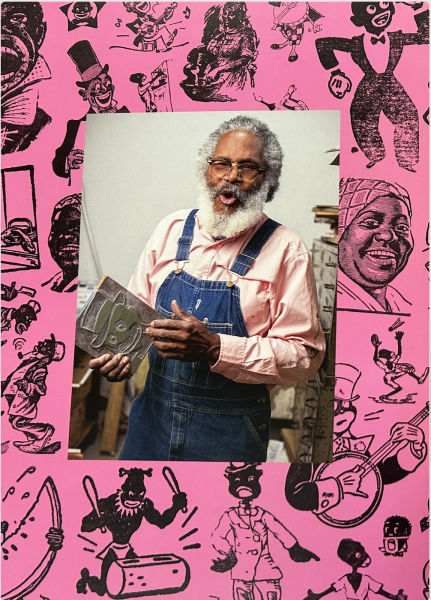

The language and imagery in his prints heavily feature the history of oppression, and the effects it still has upon African Americans today. Purposefully, he collects antique woodcuts created to degrade African Americans, which were used in press printing for over 100 years. The depictions rely on the racist and outdated stereotype that paints people of color as ‘savages’. The woodcuts—and the stereotype—not only dehumanize people of color but attempt to erase them from society.

By utilizing them in his prints, Kennedy actively takes back the power that African Americans have been stripped of. Before slavery, he told participants, “they may have been called African – but not Black.” Kennedy, being born in the 1950s, was labeled “colored” on his birth certificate.

The conversation shifted to the power of language—and having the right to speak up for one’s own rights.

“Don’t give up your power. Maintain your power- don’t compromise it. And if you do compromise it, use it to better yourself,” Kennedy told the room. “When my boys were little and it was their bedtime, I gave them a choice; they could go to sleep, or I could read them a bedtime story. Now, despite them having the power to choose, either way, they still were going to bed.”

After the discussion, students shifted into the creation process of printing, seeing firsthand how important topics can be incorporated into art. Kennedy asked participants to build on the experiences they have had with erasure in their work.

While everyone considered and created the bottom layer of art, Kennedy set up the press to print ‘Day of Dialogue’ over their written words.

Kennedy created a spark within the MCLA community with a conversation about the obligations we have to the world—as both a citizen and as a human. Racism, as Kennedy reminded everyone, is still a prominent force in modern society, and it is up to each and every person to work against perpetuating it into the future.

If you would like to join this conversation, and or would like to see the messages that Kennedy creates within his pieces, you can look into his book “Citizen Printer,” or visit his website at www.kennedyprints.com.